In late summer of 2017, I set out on a five hundred mile walk on the French Way of the Camino de Santiago. In a journey which challenges able-bodied individuals, I had to confront the added burden of having the neuromuscular disease called Becker muscular dystrophy. Although I was no stranger to weekend backpacking trips, the Camino would be a hike longer than anything I had ever attempted. With an unexpected approval for the time off from work, I jumped on the opportunity with no idea if my body could hold up. For someone with my condition, most doctors would consider hiking five hundred miles ill-advisable. I knew my condition was progressing and another few years might put the Camino outside of my abilities. For me, the Camino would be a chance to discover my own definition of strength.

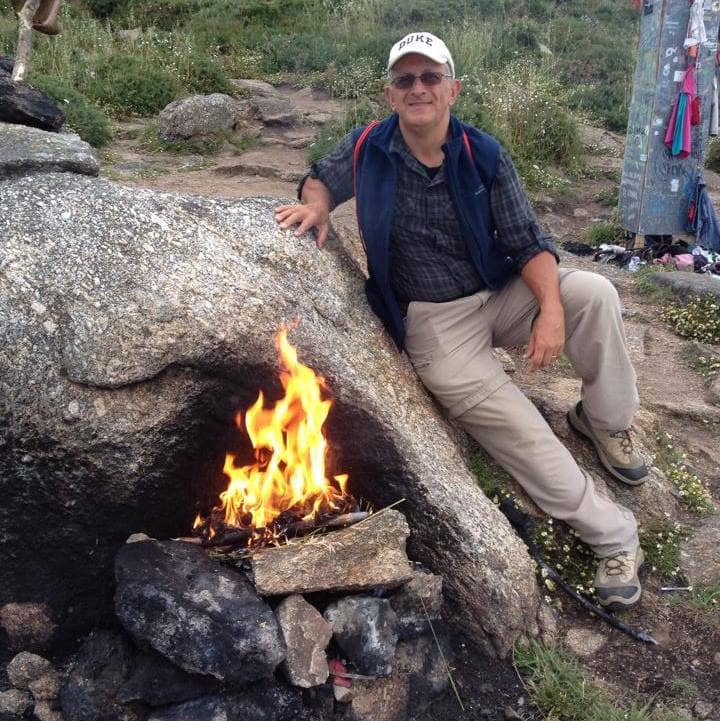

The undertaking was enormous, but most of my physical difficulties were predictable. In sections through the Pyrenees and Galician Mountains I was forced to occasionally crawl, drag my pack, and rely on passing pilgrims to lend a hand. Although the physical aspects were grueling, it was actually the mental aspect that proved to be the most challenging. Even though I took 46 days, nearly two weeks longer than the average pilgrim, the Camino was still five hundred miles under my feet. There were no elevators over mountains or ways to hide from my disability, so muscular dystrophy was on my mind for every step from St-Jean to Santiago. Due to this reality, I was forced to break with one of the oldest Camino traditions. At the monument known as Cruz de Ferro, three hundred miles in, pilgrims are expected to leave a rock at the iron cross at the top of a hill. The rock represents leaving behind a burden one has carried from home and onto the trail. When I thought about my burden, I realized it was muscular dystrophy. There was no way to physically leave this behind, so I needed to redefine what my rock represented.

The rock I brought was from the top of a mountain named Medicine Bow Peak in Wyoming. When I climbed the mountain in 2013, it had been the biggest physical challenge of my life. The rock became a memento of the courage I needed to reach a goal. Every time I held the rock in my hand, I remembered the strain in my muscles as I climbed toward the top of the mountain. But the more I thought about the rock on the Camino, the more I realized it was just a rock. I did not need a rock to represent my capabilities. As soon as I declared the rock a symbol of strength, it represented nothing. What I sought on the Camino was to embark on an adventure while my body still allowed it, and that meant embracing truth. Muscular dystrophy would be a part of me for the rest of my life. People cannot always choose their burdens, but they can choose how they carry them. When I put my rock down at Cruz de Ferro, it was not to let go of a burden, but to swap it for the truth. I let go of the past and embraced the present. Maybe a wheelchair was in my future, but I was headed there no matter what. The only other option was a dark path of denial.

Despite coming to terms with what muscular dystrophy meant to me, I still struggled with how my slow pace affected the friendships I made on the Camino. Finding steady company proved difficult when I moved at half the pace of other pilgrims on steep sections. A group of pilgrims who accompanied me over the Pyrenees realized staying with me for an extended period would cost them reaching Santiago within their time frame. Their initial separation from me was difficult, as I relied heavily on reaching for a hand on difficult sections of trail. When I explained the predicament of my slow pace to another pilgrim, an older man named Don from South Carolina, he said, “Slow? There is no such thing as slow on the Camino; there is only your own pace. We all have our own difficulties, and we all deal with them in our own ways.”

Don’s words resonated with me for the rest of the Camino. Focusing on my own pace would become my mindset as other pilgrims came in and out of my journey. Feeling sad about other pilgrims leaving me was natural, but everyone had their own path to follow. The difficulty people have in focusing on their own pace in life relates to the problem of understanding strength. Most people, including myself, see themselves as weak in comparison to someone who is stronger or more physically capable. On the Camino, I realized that the idea of being weak only holds true when we compare ourselves to others. Strength should not be a linear measure, but rather a reflection of your own will to persevere. When we face challenges from our own unique reference point and not through the eyes of others, we become truly strong. The more pilgrims I met, the more I realized that my disability did little to define me. I began to reflect further on Don’s wisdom about everyone dealing with their difficulties in their own ways. The Camino has a tendency to become a haven for people “figuring out their lives.” There are pilgrims who walk to deal with grief and others who simply seek to rediscover meaning in lives. The only thing to do on the Camino is to find a path that works, whether you have to be carried or crawl.

When I finished the Camino in October, I was thrilled to have reached my goal, but something was missing. Santiago did not feel like an end, nor did it feel like a beginning. Whether it was because I felt insignificant among thousands of other pilgrims at the end or because I was not ready to return home, the lack of a triumphant feeling continued to haunt me. The next summer I returned to the Camino to chase this undefined feeling. This time I hiked the Coastal Portuguese Way from Porto, but I was to walk beyond Santiago this time. After hiking 174 miles to Santiago, I planned to hike an additional one hundred miles of trails to the coast and around Galicia. Although my time on the Portuguese Camino had its share of struggles and triumphs, the journey lacked the moments of true inspiration from the year before. When I reached the coastal town of Finisterre, 54 miles beyond Santiago, I stood on the edge of a rocky peninsula watching the waves crash against the land. In Latin, Finisterre, or “finis terrae,” directly translates to “end of the earth.” Long before the Camino, ancient Celtic tribes believed this location was the end of the world. Something about this place felt like the end for me too. “I want to go home,” I said out loud to myself.

There was no reason to walk any additional trails around Galicia. I realized the Camino taught me everything I sought to find. True strength was about standing at the edge of something bigger than yourself and knowing that nothing but your own inner grit brought you there. This was what I discovered at Finisterre. After walking 730 miles throughout Spain and Portugal within a year’s time, the only place to go was home.

For a full account of my journey on the Camino de Santiago, be sure to read my blog here.